I just committed to buy my first-ever season pass to ski and snowboard at Steamboat. It didn’t even occur to me that for many reasons right now, that might have been stupid.

The ‘many reasons’ run the gamut, from finances and new work projects to personal, emotional, and oh, yeah, that little thing about my surgery. In March I tore my calf and Achilles, got stitched up, went four months without walking on two legs, and now can’t wait to strap back into that snowboard. Meanwhile, I’m starting a new chapter in my life. In a nutshell (so we can get on to more interesting things), I’m sweating finances while trying to maintain the signature enthusiasm that seems to be paying off in my writing work lately. This winter I’ve chosen to cultivate that enthusiasm by living near my mountain condo in Steamboat Springs, Colorado (which is a rental, meaning I can only stay here between paying guests). I got a taste for this lifestyle over three months last fall while wrapping up the first draft of the forthcoming book, Living Richly.

Of all the things I’ve done this year, two stand out as providing a pure sense of joy: carving turns on the mountain and making these little black marks on your computer screen. Occasionally I wax poetic about that similarity: how good days skiing or snowboarding are a lot like writing, in that you leave your mark on a pristine white surface. Signatures, a new ski film this season, set in Japan, plays with this very notion.

You say: “That all sounds peachy, but where’s the bravery? Where’s the stupidity?” I take a break to think about it, fetching my arnica oil and massaging it into the dull ache just beneath my new three-inch scar. Ah, that’s it: skiing and snowboarding are ways to leave your mark on the world— and ways the world can leave its mark on you. It’s not insignificant that tomorrow night I’ll see a little of the late great Arne Backstrom in the premiere of the new Warren Miller film (he also skied for other movie companies, including Sweetgrass, makers of Signatures). Backstrom died this year while leaving his mark on the mountains of Peru.

I’ve skied my whole life: it’s gotten to where the life- and limb-threatening aspects of my sport rarely cross my mind. Perhaps that’s why we occasionally have to get stupid: to remind us what we’re doing. End-of-year parties at ski resorts do just that: racing down the mountain in cardboard floats, skimming across icy ponds in coconut-bikinis, shots of tequila before backflipping into the hotel pool (not me, but I’ve met a few) … If we’re going to risk our lives for something we love, it oughta be exhilarating, right? Not just this sappy poetry about carving undulating calligraphic arcs down the smooth white skin of mother mountain.

I’ve skied my whole life: it’s gotten to where the life- and limb-threatening aspects of my sport rarely cross my mind. Perhaps that’s why we occasionally have to get stupid: to remind us what we’re doing. End-of-year parties at ski resorts do just that: racing down the mountain in cardboard floats, skimming across icy ponds in coconut-bikinis, shots of tequila before backflipping into the hotel pool (not me, but I’ve met a few) … If we’re going to risk our lives for something we love, it oughta be exhilarating, right? Not just this sappy poetry about carving undulating calligraphic arcs down the smooth white skin of mother mountain.

The silly stupidity of springtime ski resort antics, like the satire of The Onion, allows us to look our everyday absurdity— and dangerous behaviors— right in the eye. Chasing a passion that could kill you, bankrupt you, or turn you into another twitchy mountain-town freak might be called absurd before it was called brave. Yes, putting a plank or two on my feet and navigating down snow and ice on a steep mountainside, that’s a bit of an odd calling. Like men elbowing each other to steal an orange bouncy-ball and hurl it at a metal ring attached to a board. The only difference is that skiing’s occasionally dangerous and actually cool and basketball— well, I better stop there.

When I dropped my desk job to become a freelance writer, people told me how brave that was. I hadn’t thought of it that way. Now I realize it was a departure from the norm, a risky endeavor, an exhilarating challenge. To make sure we don’t lose sight of our everyday acts of bravery, I recommend frequent acts of stupidity.

Thanks for reading. Cheers,

P.S. In honor of the 100th anniversary of scouting, this is blog no. 10 in a 12-part monthly series on the Boy Scout Law. Today: “A scout is brave.”

Photos by Boo-Creative

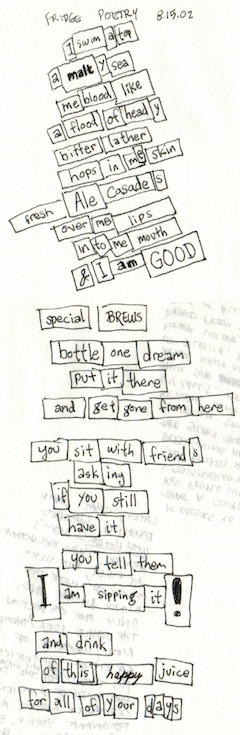

As part of my two-years-long-and-counting spring cleaning exercise, I’m thinning my archives. There’s enough paper to make a papier-mâché blue whale and a shredded sea for it to swim in.

As part of my two-years-long-and-counting spring cleaning exercise, I’m thinning my archives. There’s enough paper to make a papier-mâché blue whale and a shredded sea for it to swim in.![]()

UC Santa Cruz @ Oregon — The Ducks are serving up a 72-0 feast of the Banana Slugs when UCSC mascot, Sammy the Slug, tires of his diet of native rhododendrons. His victim, a sullen webfoot cheerleader, was caught unaware while longing for sunnier days in her native Arizona.

UC Santa Cruz @ Oregon — The Ducks are serving up a 72-0 feast of the Banana Slugs when UCSC mascot, Sammy the Slug, tires of his diet of native rhododendrons. His victim, a sullen webfoot cheerleader, was caught unaware while longing for sunnier days in her native Arizona. Florida @ every team they play all season — Albert E. and Alberta Gator make a new name for their struggling Florida franchise (What? Not Top 5?!) by mercilessly consuming each opposing team’s entire pep squad in the first quarter. Only

Florida @ every team they play all season — Albert E. and Alberta Gator make a new name for their struggling Florida franchise (What? Not Top 5?!) by mercilessly consuming each opposing team’s entire pep squad in the first quarter. Only  I’ve skied my whole life: it’s gotten to where the life- and limb-threatening aspects of my sport rarely cross my mind. Perhaps that’s why we occasionally have to get stupid: to remind us what we’re doing. End-of-year parties at ski resorts do just that:

I’ve skied my whole life: it’s gotten to where the life- and limb-threatening aspects of my sport rarely cross my mind. Perhaps that’s why we occasionally have to get stupid: to remind us what we’re doing. End-of-year parties at ski resorts do just that: